di Barbara Martusciello

Andiamo con ordine: è il 1968 quando l’Architetto Carlo Aymonino chiama Aldo Rossi a collaborare al quartiere di Gallarate che la Società Monte Amiata gli aveva affidato pochi anni prima. Rossi vi lavora dal 1969 al 1973 e concepisce un corpo di fabbrica in linea di 185 metri di lunghezza, profondo 12 metri, a tre piani fuori terra con un’altezza complessiva di 12 metri. E’ come “una lama che entra dentro il groviglio dell’impianto di Aymonino”, dice lo stesso Aldo Rossi (in: “Quaderno Azzurro 2”, 26 novembre 1968, in: Aldo Rossi, “I Quaderni Azzurri 1968-1992”, a cura di Francesco Dal Co, Electa/The Getty Research Istitute, Milano 1999). La consueta casa a ballatoio diventa qui, con Aldo Rossi, qualcosa di riconvocato e al tempo stesso nuovo, dalla forma di un rettilineo continuo, schiuso su un lato, che organizza i singoli alloggi. “L’intensa traduzione e rilettura espressiva della tipologia delle case a ballatoio si somma a suggestioni, riferimenti, immagini” che inseguono la ridefinizione della costruzione di luoghi: “dentro un edificio”, a confronto “con la città e, nelle immediate vicinanze, con gli edifici di Aymonino”; e un luogo come “interpretazione concreta dell’abitare”. Se abitare l’architettura era la funzione, abitare l’Arte è il motto di Orlandi che ce lo riporta con fotografie digitali nette, poco lavorate in post-produzione, cromaticamente sature e accattivanti. Lo sguardo del fotografo trasforma un’estensione domestica in qualcosa di lievemente straniante, persino inquietante: come non pensare, guardando il lungo attraversamento a corridoio di alcune foto, alla scena di “Shining” (1980), uno dei cult di Stanley Kubrick? Diversamente declinato, quel percorso ritorna nella filmografia del regista come topos (“001 Odissea nello spazio”, 1968). Kubrick, che fu, tra l’altro, anche talentuoso fotografo, sosteneva che se qualcosa: “può essere scritto, o pensato, può essere filmato”; quindi, con Orlandi, “può essere fotografato”, e reso qualcosa di essenziale, mentale e semplificato. Concordiamo con Bruno Munari: “Complicare è facile, semplificare è difficile. Per complicare basta aggiungere, tutto quello che si vuole: colori, forme, azioni, decorazioni, personaggi, ambienti pieni di cose. Tutti sono capaci di complicare. Pochi sono capaci di semplificare. Per semplificare bisogna togliere, e per togliere bisogna sapere che cosa togliere (…). Togliere invece che aggiungere vuol dire riconoscere l’essenza delle cose e comunicarle nella loro essenzialità. (…) La semplificazione è il segno dell’intelligenza, un antico detto cinese dice: “quello che non si può dire in poche parole non si può dirlo neanche in molte”.

Translated by Michele Rosi

Claudio Orlandi has grown up. Like everybody he has improved his phrasing, supported by a photographic grammar that transforms the figurative expression of reality into abstraction.

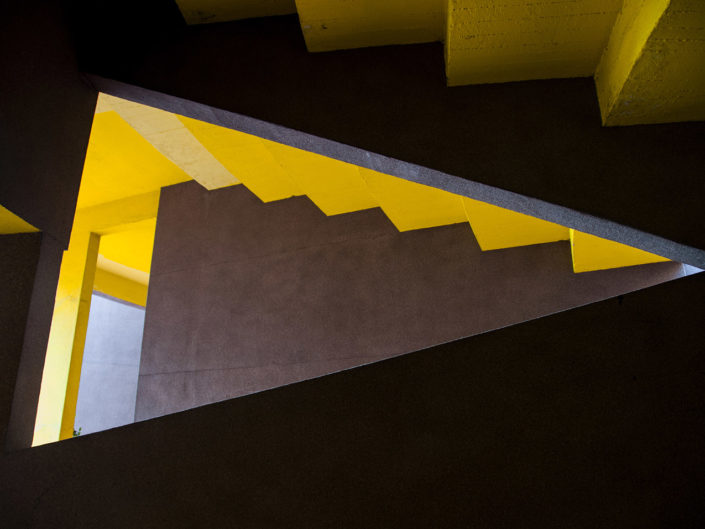

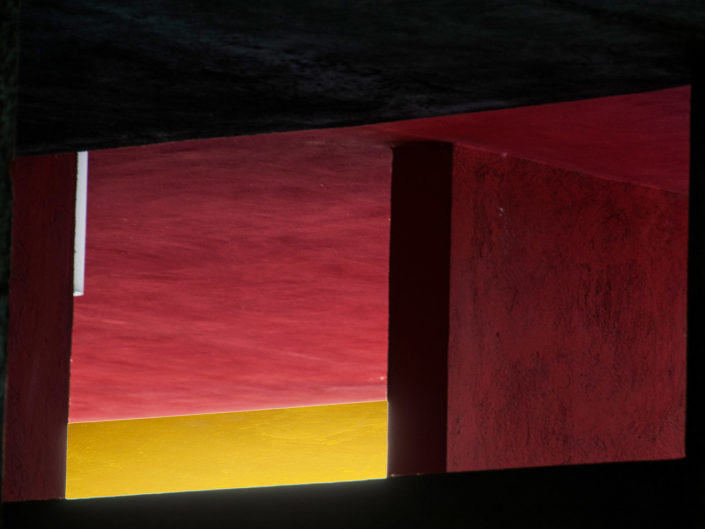

His work here is focused on the transformation of architecture that, from simple “containing prop” and outside-inside physical and psychological bridge, becomes in his pictures a chance to make considerations on colour, on those concepts of structure and geometry and a recall to that Abstractionism which fascinated authors like Franco Fontana and Gabriele Basilico. This author, in fact, returned with his lens that Gallaratese neighbourhood which, at the end of the sixties, saw the architect Aldo Rossi standing out, exactly the person which would seem the perfect “Virgilio” evoked by Claudio Orlandi to accompany him in his exhibit entitled “The Castle”. But first things first: it’s 1968 when architect Carlo Aymonino engages Aldo Rossi for a collaboration in the neighbourhood of Gallarate that just few months earlier was entrusted to him by the Monte Amiata society. Rossi works there from 1969 to 1973 and conceives a line of factory buildings 185 meters long, with a depth of 12 meters, three levels high for a total of 12 meters. It resembles “a blade that penetrates the tangle of Amonino’s plant”, says Aldo Rossi himself (in: “Quaderno Azzurro 2”, 26 November 1968, in: Aldo Rossi, “I Quaderni Azzurri 1968-1992”, by Francesco Dal Co, Electa/The Getty Research Istitute, Milan 1999). Here the classic walkway house becomes, with Aldo Rossi, something re-evoked and new at the same time, shaped as a continuous straight path, open aside, that organizes the single apartments. The continuous reference by Rossi to all those constructions belonging to the traditional Milanese house is for sure one of the generating themes of the project. The intense translation and expressive reinterpretation of the walkway house category sums up with suggestions, references, images trying to define the possibility of construction in a given place; a place inside a building, a place capable of confronting itself with the city and, nearby, with the surrounding buildings of Aymonino; a place, again, able to become the concrete interpretation of living.

Living the architecture was the purpose, living the Art is Claudio Orlandi’s motto that he expresses with quite neat digital pictures, not too manipulated in post-production, highly saturated and charming. The gaze of the photographer transforms the domestic setting into something slightly unsetting, even disturbing: how couldn’t you think, looking to the long crossing corridor, to the “Shining” movie scene, one of Stanley Kubrick’s cults? A journey that, declined differently, returns in the filmography of the American director as a “topos” (2001 a Space Odissey, 1968). Kubrick was, among other things, also a talented photographer; he claimed: “If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed”; we close up by claiming, then, it can be “photographed” too: but expressed, as Claudio Orlandi does, as something essential, mental and simplified. Yes, we agree with Bruno Munari: “To make something complicated is easy, but to make it easy, it’s complicated”. To make something complicated it is sufficient to add, whatever you want: colours, forms, actions, decorations, characters, and rich environments. Everybody is able to complicate things. Only few are able to simplify. To simplify you have to subtract and you have to know what to subtract. Subtracting means recognizing the essence of things and communicating them in their spirit. Simplification is evidence of intelligence, like an ancient Chinese saying says:” What cannot be told in few words, cannot be told with many words either”.