di Barbara Martusciello

In questo contesto, attraverso lo sguardo fotografico di Claudio Orlandi (…) possiamo riconsegnare immagini di materiali lapidei maneggiati appositamente per diventare parte della città, che nella fattispecie è Roma. Di questo territorio, la straight photography 1 (…) anatomizza solo costruzioni moderne e contemporanee: per allontanarsi da significati aggiunti, che la remota storia porta con sé ed evoca, e da una visione oleografica che quasi fatalmente la Capitale sollecita. Prescindendo dalla sua ricchezza e delle sue declinazioni antiche, ci interessa, pertanto, una considerazione che tenga conto delle più odierne entità fisiche costruttive urbane e delle tensioni dinamiche correlate di cui le foto qui esposte ci danno un’estrema sintesi geometrica.

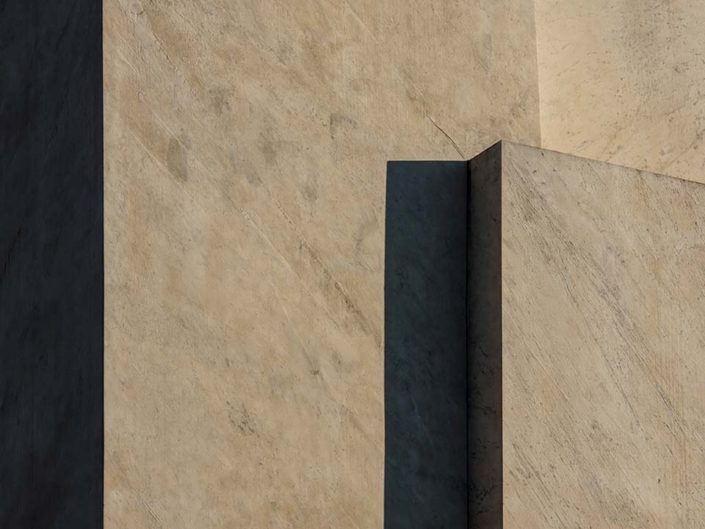

Pietra e astrazione, insomma, (…). Claudio Orlandi modula i contrasti cromatici, attenua o esalta porzioni dello spectrum (2) con calibrato equilibrio, indicando piani e superfici a richiamare l’astrattismo pittorico (…).

In tutte le immagini è cercata la ritirata dalla Fotografia più strettamente realistica, dalla figurazione, dal bel panorama… La riconoscibilità delle strutture rappresentate e, anzi, tutto l’insieme che le connota come architetture identificabili, non sono più – e volutamente – agili perché è favorita l’ambiguità che emerge grazie al peculiare punto di vista (…). Che si tratti del Foro Italico (…) ha poca importanza (…): quel che (…) spicca è ciò con cui tali manufatti sono prodotti o ricoperti – travertino, granito, ardesia, tufo, marmo, porfido – e il loro manifestarsi attivatori di porzioni di astrazione, di ritmo e combinazioni schematici.

Vediamo, pertanto, immortalate delle “impalcature matematiche” che – come giustamente già affermava Salvador Dalì – non “uccidono” la magnifica “aspirazione dell’artista” per la fallace idea che esse siano troppo essenziali e irrigidite; diversamente da quanto da lui ipotizzato, però, tale griglia geometrica non è escamotage a cui affidarsi come “guida alla simmetria” e per “non avere da pensare e riflettere”. La scelta visiva praticata da (…) Claudio Orlandi (…), anzi, innesca il “pensiero” e accompagna proprio alla “riflessione”: scattando su edifici dove – abbiamo detto – la pregnanza litica è consistente, ci consegnano la (…) ricerca certosina del particolare, il singolare orientamento diretto alla decontestualizzazione figurativa in funzione di una sintesi e di un minimalismo compositivi; ed è proprio grazie a questa posizione selettiva, minuziosa, trasversale e analitica (…), che si crea un approdo a un nuovo protagonismo del materiale. Esso si evidenzia sia a livello fisico, reale, sia poetico, concettuale. Non solo. Si palesa il dialogo proficuo tra Estetica e Spazio e tale colloquio, ricomposto nelle (…) belle, nette fotografie, è motivo di novella conoscenza: e, per citare ancora il filosofo maestro (Platone), in fondo in fondo, “La conoscenza che la geometria cerca è quella dell’eterno.”

Translated by Michele Rosi

Was the great philosopher Aristotle wrong when he claimed (in his Nicomachea Ethics, second Book, IV century b.C.) that “Nothing of which is by nature can take on habits contrary to itself: for example, the stone which by nature moves towards the ground cannot get used to move towards the sky, neither if you would get it used by throwing it up a thousand times”? If we read this excerpt only considering the reference that Plato’s disciple makes to the stone (we would be wrong to limit our reasoning to this, but let us give us this limitation by now), we could affirm that yes, he was wrong. Why? Because we know how much the stony material is moldable and how men managed to conduct it towards the sky, challenging gravity. Such a constructive recklessness held out through times and when it disastrously free fell it was because of distraction, lack of expertise or guilty human malice. So the stone, in all its typologies, “stays up” in architecture: both in the case of solid stone, structural realizations – very common in the past – or as upholstery, more or less thick, of buildings of the twentieth century, that in the most recent design allow for more and more intrepid experimentation.

In this context, through the photographic gaze of Claudio Orlandi we can give back images of stony materials, molded to become part of the city of Rome. About this territory, the straight photography 1 deconstructs only modern or contemporary buildings: to walk away from added meanings, that the distant history takes along and evokes, and gives an oleographic perspective that, nearly fatally, the Capital solicits. Regardless of its abundance and ancient declinations, we are therefore interested in a consideration that accounts for the most current constructive urban entities and the correlated dynamic tensions of which the pictures here displayed give an extreme geometric synthesis.

Stone and abstraction, then, Claudio Orlandi modulates the chromatic contrasts, diminishes or exalts portions of the spectrum, with calibrated balance, pointing plans and surfaces to recall pictorial abstractionism.

In all the pictures the most realistic aspect of Photography is sought, from the figuration or beautiful landscapes… The recognisability of the represented structures and the whole set connoting them as identifiable architectures are no nimble anymore, because this time the ambiguity rising from the peculiar point of view is preferred. The fact that we are dealing with the Foro Italico is not important: what stands out is what those works are covered with or made of – travertine, granite, slate, tuff, marble or porphyry – and their manifestation as portions of abstraction, rhythm and schematic combinations.

We see eternalized, hence, some “mathematic scaffolding” that – how Salvador Dalì already correctly claimed – does not “kill” the magnificent “artist’s aspiration” for the faulty idea that they are too essential or stiffen; differently from what he had hypothesized, however, such a geometric grid cannot be an escamotage on which to rely as a guidance to symmetry and to have none to reflect upon.

The visual choice carried out by Claudio Orlandi, on the contrary, triggers “thinking” and accompanies to “consideration”: shooting buildings where stony presence is abundant delivers the painstaking research of the detail, the singular orientation directed to put figuration out-of-context in favour of a compositional synthesis and minimalism; thanks to this selective, meticulous, transversal position, the importance of the material becomes crucial. It highlights itself at a physical, real, poetical and conceptual level. Not only. It appears the fruitful dialogue between Aesthetics and Space which, recreated in the neat and beautiful pictures is reason of spring knowledge: and, to quote again the master philosopher (Plato), “The knowledge sought by geometry is the one of eternity”.

Sadakichi Hartmann, A Plea for Straight Photography, in “Camera Work”, 1904

Roland Barthes, La chambre claire, Gallimard, Paris, 1980